The current Iditerod commemorates that amazing feat.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Palmer, Alaska

Monday, July 25, 2011

Little Susitna River and the Independence Mine

"The mine was operating from 1937 until 1941," she began. "It was around 1941 that Pearl Harbor happened, and everyone got nervous, because, if you know your geography, Alaska and Hawaii are real close."

Silence. What did she just say? "Around 1941"? How about exactly December 7, 1941? And Alaska DID feel threatened, but not because they thought the Japanese might make a lefty at Hawaii and beeline for the Hatcher Pass in Alaska -- but because Japan was just 2000 miles away from the Aleutians, that curving string of islands that juts out from the southwestern edge of Alaska and almost reaches Russia. Landing in the Aleutians (which they did in June 1942) would give them a base in North America from which to launch further attacks. And the mine didn't close in 1941 -- it operated for a couple years under a war-time exemption (other gold mines were deemed non-essential in wartime and closed) because, in addition to gold, this mine was a source of tungsten which was deemed essential. It was, however, eventually closed in 1943, not 1941.

FYI:

Tokyo to Honolulu: 3860 miles

Honolulu to Anchorage: 2780 miles

Move men and planes 6640 miles or 2000 miles? Which would you choose?

So we were off to a humorous, if unbelievable start. Fortunately, she knew a bit more about the mine than she did of what was, from her 20-something perspective, "ancient history," but she lacked even that information unless it was in her tour. Her stock answer to most questions was, "I don't know" accompanied by a quick return to her script.

Still, we enjoyed seeing the dining room and living quarters, and we got a feel for what a miner's life was like. The mine housed and fed around 200 men, each earning $8 a day for 8-10 hours of hard work. Unless you managed the mine, the best job was the chief cook, who got his own sleeping quarters, bathroom (with a tub), kitchen, and sitting room, all with no deduction from his pay. The miners had a cot in a barracks-like room, showers "down the hall," and communal dining for which they paid $1.50 per day. When we got to the school building (it was for 8 children from miner families who lived in nearby Boomtown), we gave up all pretense of following our guide -- she stood at the front listening while John used a wall map to explain the mine's relationship to the Cook Inlet:And I used a classroom globe to show a curiosity that can be found on many old globes: manufacturers used to fill that huge empty space in the Pacific Ocean with an analema. An analema looks somewhat like a figure 8, but is actually a representation of the path that the sun transcribes in the sky. If you were to take a photo of the sun at the same time each day for a year, the resulting pattern would be the analemma:

We finished the tour, and as we returned to our car this little ground squirrel was eating vegetation: Consider this your "Obligatory Cute Mammal Shot"!Saturday, July 23, 2011

Devil's Canyon Whitewater

We stopped at a recreation of a Dena'ina Indian encampment and trapper's cabin, where John got to show off new "head" gear:

We saw a couple bald eagles and a now-large chick (in the nest): When we got to the beginning of the canyon, the rapids picked up... well, rapidly: But the peak of the trip was when our captain held the boat in place so everyone could have their picture taken with the whitewater as a backdrop. We did not run the rapids -- only two boats have ever successfully done that. But it sure was a thrilling sight to see all that water madly rushing towards us while we watched from the safety (and dryness) of the boat.Friday, July 22, 2011

The State Insect of Alaska

It is the dragonfly, in particular one named the Four-Spot Skimmer. I have not yet seen a Four-Spot Skimmer here, but I did see this dragonfly last night:

This is a Zizgag Darner, Aeshna sitchensis. (Identification by my friend, Richard Orr -- thanks, Richard!)I found the Darner last night after he landed on a paver in the RV park here in Willow, AK. I kept walking closer and closer to him, and he didn't move. Finally I was so close I was able to put my finger on his wing and he was trapped. I thought he was probably so easy to catch because he was injured, but he seemed perfectly fine.

So I grabbed him by holding his wings together, and off he went into the rig for his close-up photography session (I did warn John that the possibility existed that "dragons would be airborne in the rig," but he didn't seem to mind). The Darner quieted down nicely after a few minutes in the fridge, and held a pose long enough for me to take these photos.

And yes, the Darner did survive his first photo session/refrigeration ordeal. I released him, and watched as he flew into the sunset to finish his dragonfly business. Incidentally, we actually do have a sunset now, although it is still not completely dark -- there is at least a faint glow of light in the sky all night. The visible daylight is down to "only" 20 hours, 55 minutes, and we do not have a nautical or astronomical twilight. I have gotten used to sleeping with a light sky, but I still find myself staying up very late as there is no darkness "cue" to tell me to get sleepy. Good thing the Internet is always there to entertain me!

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

The Flight Over Denali

When we got up this morning, the sky was a clear, cloudless blue. From our viewpoint in Talkeetna, Denali, still 60 miles away, was a sparkling, shimmering jewel. Weather here is quickly changeable, but we knew we had a beautiful day for our 10:30 flight to see "The Great One" up close.

As instructed, we got to the airport before 10 and spent some time chatting with the other fliers and watching the planes and helicopters. By the time we took off at 10:30, high cirrus clouds had set in and the summit of Denali was obscured, but everything else was still in the open.

Our plane was a 6-seater Piper. Our pilot, Dale, briefed the four of us (John and me and another couple) on safety features of the plane -- how to open the plane's door from inside, where the emergency food and water was stashed, and how to buckle a safety belt. Really, is there anyone on the continent who doesn't understand how to buckle a safety belt? We got in, donned our headphones, and took off.

Northbound, we followed a braided stream whose source is a glacier on the mountain:

Once we got near Denali and its next-highest neighbor, Foraker, we saw several huge glaciers, rivers of white ice and brown accumulated dirt, winding their way through mountain valleys. One of these glaciers, Ruth Glacier, is almost 4000 feet deep and can move 3.3 feet per day!The summit was still mostly fogged in, but we did catch brief glimpses of it as our pilot circled through the snow-covered peaks. The only brief feeling of "uh-oh" came when he told us he was going through a pass, and asked us not shift our weight during the maneuver. When a pilot says that, it is very easy to sit perfectly still! A bit of turbulence and we were through it. My Dramamine did not let me down.

The climbing season on Denali is now over -- Dale showed us where base camp is, but all that remained today was a few ski marks from the planes that had dropped off climbers.

Here is a map of our route that Dale drew after we landed. He said the lines look like a moose -- he must be a fan of Picasso: To be so close to such "magnificent desolation," (a Buzz Aldrin quote about the Moon but I feel it is also appropriate for Denali), is to feel the surreal. The snow sat in unimaginable depths on the peaks. On the glaciers we could see rock falls on top of blown dirt, all on top of the packed ice which was laced with huge blue crevasses, created by the glacier's slide inexorably downward. We saw the glacier's face change from new-snow white, to dingy grey ice, to a covering of brown blown dirt, and finally to green from the trees that astonishingly grow in the dirt on the ice. We saw the inhospitable places where fellow humans ventured, and tried to imagine what it was like to stand there at base camp in howling winds and freezing temperatures, to follow the trail over ice flows and around house-sized rocks, and to climb that thin ridge of snow and ice to make the summit. Words are such a poor representation of the experience. It was awesome. Just awesome.Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Talkeetna Oddities, Hatcher Pass, and We Are Run Out of Town

Talkeetna Oddities

"Village Arts and Crafts" = Maybe the "Human Arts and Crafts" are done indoors.

Talkeetna has pasties (pronounced PAST-ees), just like Michigan's Upper Penninsula! They both have the same origin -- Welsh/Cornish miners. Pasties were pies made from left-over meat and vegetables that the miners' wives gave them to take into the mines for lunch. We had to try a couple -- we got one beef and one salmon (not so traditional in the U.P.!) We ate the beef one this morning -- just like in Michigan, I liked it, John didn't.This is just asking for trouble:

On the left, "Parking," on the right "No Parking Spawning Only."This is the historic Fairview Inn:

A native woman outside the Inn told us to be sure to go in to see "the polar bear on the ceiling." This is what we saw when we went in: At least it WAS on the ceiling.Hatcher Pass

We made some new friends while we were in the campground in Fairbanks. They told us not to miss the drive through Hatcher Pass (it is also called the Willow-Fishhook Rd). They were so right! What a gorgeous drive (but NOT for RVs!).

We began at the Willow side, and followed Willow Creek for several miles.

The road went from paved to mostly-good packed dirt, although some stretches were a bit rough and lacked any type of guardrail. We climbed high over the valley floor and way above the tree line for some amazing views. After about 40 miles, we went through the pass and came out near Wasilla. We highly recommend this drive for anyone in the area.We Are Told To Move Along

Our campground is smack dab in the middle of Nowhere Alaska, a place where old cars, older RVs, appliances, and metal objects of questionable origin come to die. And they all die in the middle of their last owner's yard, ostensibly to remain there until the rust destroys them or an earthquake covers them, whichever comes first.

We told our campground owner we were going for a walk, and she suggested we walk "around the block," the roads all being dirt lanes through the forest, and practically unused. This was our general direction of movement:

As we walked, we saw many "driveways" (i.e., rutted tracks) that led to "houses" (i.e., falling down structures or 30-yr old RVs covered with torn blue tarps), with vehicles that were decorated with rust, every crack filled with weeds, and sitting on four flat tires. We made a game of guessing whether anyone actually lived in these structures or if they were abandoned.Then at point A on the map, a dog came to the road to greet us. He had a collar, and seemed well fed. He didn't bark, just stared. John made "good puppy" noises. The dog kept staring.

We continued on. He shyly lagged behind us for a while, but then found some courage and passed us as if to show us the way. He stopped periodically, of course, to sniff the weeds on the edge of the road and water the fireweed. But he seemed to enjoy our company, and we were happy to have him with us.At point B, our Threesome of Bliss was shattered -- the posse arrived!

The chihuahua was the troublemaker from the start. The beagle was happy to meet our friend (they did the SmellMe-SmellYou routine), but the chihuahua would have none of it -- he wanted our new friend off his turf. The beagle then decided that, while the dog was okay, we would need to leave. As the beagle escorted us to the edge of town (around the corner at point B), the chihuahua took after "our" dog. The last I saw of our brave companion he was running at a full gallop back towards his home at point A, ears flapping in the breeze, a tiny little chihuahua hot on his heels.We continued on, a little sadder to have lost such a steadfast puppy friend.

At point C, we took one last look back, and this is what we saw:

The Sheriff made it clear -- we were not welcome in Dodge.Monday, July 18, 2011

Climbing Denali

We took a day trip today to Talkeetna, famous for two things: 1) it is allegedly the town that the fictional Cicely, Alaska in Northern Exposure was modeled after and 2) it is where Denali climbers begin.

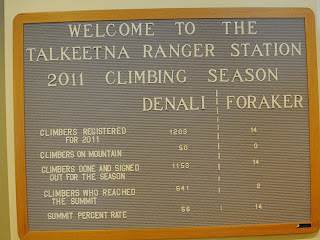

We started our visit at the Ranger's Station where all the climbers must check in. They purchase a climbing permit for $200, and the Rangers make sure that they have sufficient climbing experience to take on the often extreme conditions on Denali, where winds can be 90 mph and temperatures -40 in the summer. Here is the 2011 climbing stats to date and today's weather:

Not a bad day today at 17,000 feet -- only -15 for a low!(UPDATE: 17K is not the summit -- Denali, the highest peak in North America, is 20,320 feet)

The Rangers do keep a presence on the mountain at various camps -- a ranger and several medically trained volunteers work at the base camp at 17 K, staying there for a month at a time. They are there to help people who overclimb their abilities or have accidents, and to monitor "litter" on the mountain. They make sure that each climber has a "waste can," a contraption that holds solid human waste and is ultimately packed out by the rangers via airplane.

After visiting the Ranger station, we went to a Ranger talk next to a huge relief map of Denali and the surrounding peaks. We were divided in two teams for a game to see if we had the three things necessary for successful summiting: preparation, persistence, and luck. Each team was issued a rope to hold, an obviously necessary piece of climbing equipment, and then we drew cards to see what our "fate" was at each camp.

The opposing team made it to the summit, but -- alas -- our team did not because ravens ate our food, a hazard of mountain climbing I never heard of before! Denali has a population of ravens and tundra swan who seemingly make their living from climbers' litter. On the way up, climbers will bury food in the snow for the return trip so it doesn't have to be uselessly carried all the way up the mountain. They used to mark the cache with a flag, but the ravens soon learned that the flag was akin to saying "X Marks the Spot" or "Dig Here" -- they learned to dig under the flag to retrieve the food. Now the climbers use three flags to circle the buried cache, and so far the ravens haven't figured out triangulation!Later in the game we got caught near the summit in a snowstorm, and had to go down because we didn't have enough food to wait out the storm -- we could have summitted had we not previously drawn the "Ravens Ate Your Food" card. At least we survived! In real life, not everyone does.

Nine people have died on the mountain so far this year. Sometimes luck makes the difference between success and failure. The Ranger told a a story of a man who got within 200 feet of the summit and had to turn back because he was in danger of being blown off the mountain, and visibility was near zero. Had he pushed on to the summit he might have made it -- however, on his way down he probably would have perished in an avalanche that happened on the spot where he would have been. He missed summitting, but survived.

Sometimes persistence makes the difference. In another story, a mother and daughter team texted from the highest camp (yes, there used to be phone service there until Talkeetna took down a cell tower) that they were huddled in their tent in 100 mph winds, their backs to the tent's side to hold it all from blowing away. They stayed that way for 7 days until the storm abated, subsisting on ramen noodles. The next day they texted: "SUMMIT SUMMIT SUMMIT!"

And sometimes it is preparation. A team of three climbers set off on a steep ridge, roped together for safety. The wind came up unexpectedly, and blew one of the climbers over the edge of the ridge to the right. The other two immediately threw themselves over the edge to the left, to balance the weight, the ropes holding them from certain death. They knew what to do, and they had the right equipment to do it. They all made it.

Congratulations to the 641 who have made the summit this year, and good luck to the 50 of you on the mountain today.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Signs

In 1897, a local prospector re-named the huge mountain peak we know today as Denali to "Mount McKinley" in honor of the President -- even though McKinley had no connection to the area. The original park was also named Mt. McKinley National Park. In 1980, the park and the mountain were officially re-named Denali, although a lot of references to Mt. McKinley remain. Here is the original entry sign:

The Alaska Railroad runs though Denali, and historically was an important transportation hub for the area. Today, half the visitors to Denali still arrive by train -- that is the most common way cruise ships get visitors to the park. But how did they originally get the engines to the track? This has got to be the best name ever for a big ditch: And finally, John and I stopped at the Salmon Bake for a snack and beer: They had great antler-art: And John got one out of two instructions right! The sign outside says, "An eating and drinking landmark since 1984." Landmark? Landmarks are old things! Things our grandparents would have seen! And I was 32 in 1984, so that must make me... retired!